Posted on : Sep.29,2019 14:40 KST

Modified on : Sep.29,2019 14:44 KST

|

|

A street full of private academies in Seoul’s affluent Daechi neighborhood on Sept. 15. (Yonhap News).

|

S. Korean children shuffle through hours of private education, even on the weekends, from elementary to high school

“I’ve been going to afterschool academies since my third year in elementary school. On weekdays, it’s 10 pm by the time classes finish. On the weekends, I go to academies to memorize English sentences or answer reading questions. When I ask my mom why I have to study so much, she tells me, ‘These days they have entrance exams for high schools too.’ I wonder how long I have to keep doing this. If all the academies closed on Sundays, wouldn’t we at least be able to rest that day?”

A first-year middle school student, Choi Jeong-yun (pseudonym) told the Hankyoreh his story on the afternoon of Sept. 17 near a renowned academy in Seoul’s Seodaemun District. Jeong-yun, who had blisters around the corners of his mouth, blinked momentarily when he heard the words “mandatory Sunday closures for afterschool academies”; then he hurried off to his “next academy.” In an era where even adults enjoy a five-day limit on the workweek, children are being forced to study seven days a week.

The Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education (SMOE) announced on Sept. 19 that it was initiating a full-scale “deliberative democracy process” for the institution of mandatory days off on Sunday for afterschool academies (cram schools). One of the key pledges by SMOE Superintendent Cho Hee-yeon, the mandatory closure push is intended to “bring weekends of rest back to students” by requiring the schools to close their doors on Sundays at least. In addition to preliminary online and telephone polling to begin on Sept. 20, SMOE also said it would be completing a deliberation process through November, with an open discussion and debate by a 200-member citizen panel on the mandatory Sunday closures. Many are watching to see whether the deliberation process creates breathing room of sorts for students suffering through “entrance exam hell” – and leads to changing attitudes on students’ leisure, rest, and health rights.

|

|

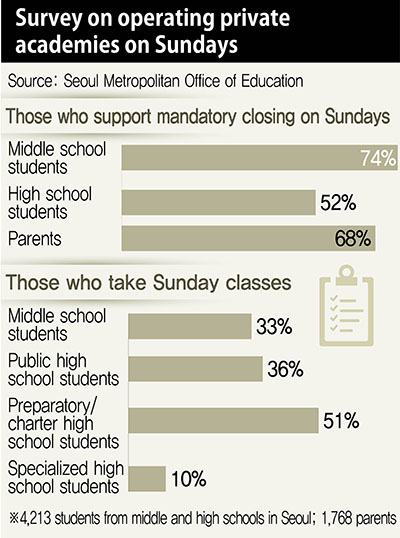

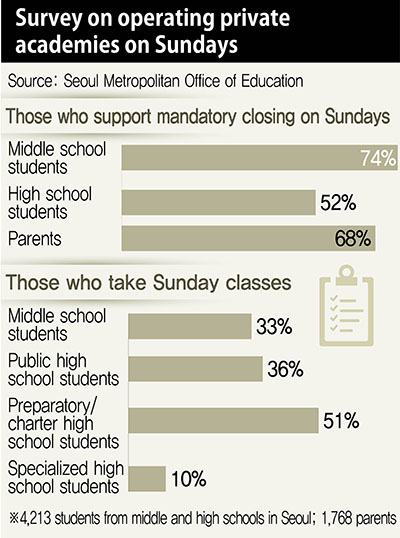

Survey on operating private academies on Sundays

|

Amid stratification in high schools as well as universities, private education spending in South Korea has risen from year to year. Last year, a total of 19.5 trillion won (US$16.33 billion) was spent on private education for elementary, middle, and high school students, an increase of 800 billion won (US$670.2 million) from the year before (US$16.67 billion). The amount is more or less equal to the South Korean government’s 2019 research and development (R&D) budget of 20 trillion won (US$16.75 billion). As the proliferation of gifted, science, foreign language, and autonomous private high schools leads to increasingly intense “high school entrance exams,” children are beginning private education at younger and younger ages; more and more are attending classes late at night and on weekends. According to a 2017 study on the introduction of mandatory afterschool academy closures and a ceiling on academy costs published by the SMOE-affiliated Seoul Education Research and Information Institute (SERII), 33% of middle school students – one in every three – attends a cram school on Sunday. The intensifying entrance exam competition for special purpose high schools has also led to growing pressure and worries for middle school students over high school entrance examinations. “Seo Hyeon-su” (pseuodnym), a second-year middle school student, explained, “I go to academies until 10 pm during the week, and I go to science and argument academies on the weekends.”

“I want to go to a science high school, but that’s more hope than anything,” Seo said with a pained expression.

Seo shared his own worries, explaining, “It’s tough to go to the academies, but I’m worried I’ll get lazy if I don’t go.” From the time they’re in elementary school, children like him are faced with studying late into the night and getting by without proper meals.

Competition even to get into renowned private academies

Home to a dense concentration of elementary, middle, and high school academies, Samho Garden Junction in Seoul’s Seocho District was crowded with children pouring out of their days around 6 pm on Sept. 18. Many of them were second and third year students in elementary school. Although it was dinner time, the children weren’t heading home; they were on their way to nearby restaurants. They were going to eat seaweed rolls, rice soup, and other dishes their mothers had ordered to have ready around that time. After gulping down their food in about 15 minutes, the children headed on to classes. “Park Ye-won” (pseudonym), a parent who lives in the area, said, “There’s a famous math academy that does a two-month advance education program for the semester, but there’s a lot of competition to get in.”

“Even when elementary students just go to English and math academies, their classes get out between eight and ten o’clock every night,” she said.

Statistics point to alarming consequences for the psychological health of children on the “academy wheel.” Around 1,600 second- and third-year middle school and second-year high school students were surveyed between May and July for a report on private education and psychological health among adolescents in Seoul’s Gangnam District. The results showed 43.1% of middle and high school students to be suffering from stress related to their studies, with 4.7% of respondents saying they had inflicted damage to their own bodies due to extreme stress and depression. A psychological counselor who has counseled many young people in Gangnam and other areas explained, “Aggression in children with pent-up stress manifests in school through exclusion and bullying of peers, and the methods are becoming more severe over time.”

“Children aren’t growing up properly,” the counselor warned.

Koo Bon-chang, head of the policy division for the group World Without Worries about Shadow Education, said, “It’s cruel to force children to attend academies on weekends at the same time that we’re trying to solve the problem of excessive working hours for adults through systems like the 52-hour workweek limit.”

Kim Jin-woo, steering committee head for the Citizen Forum for Restful Education, said, “Back when they were talking about a limit on late-night operations by afterschool academies, people worried about a ‘balloon effect’ with increased tutoring, but the number of children attending academies after 10 pm decreased by over 50% after the system went into effect.”

“Study times for students are long enough to constitute death by overwork. We need to give them days for resting,” Kim said.

By Yang Seon-ah, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]