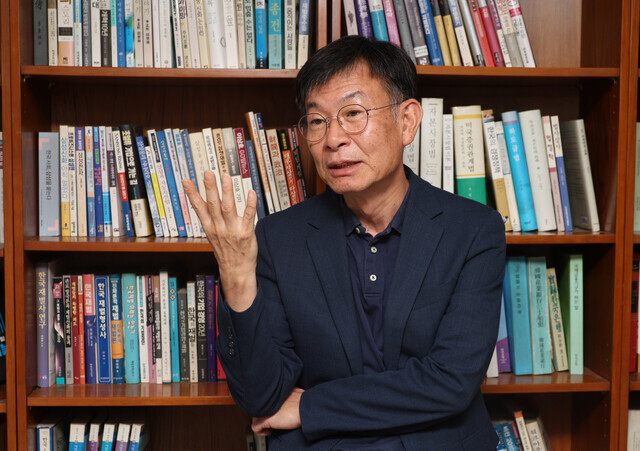

Kim Sang-jo, a former policy chief in the Blue House for President Moon Jae-in, speaks to the Hankyoreh about his new book at his office at Hansung University in Seoul on Aug. 22. (Kang Chang-kwang/The Hankyoreh)

Kim Sang-jo, a professor of international trade at Hansung University, was an iconic figure in the Moon Jae-in administration.

A civil activist during the paradigm shift in Korea’s economic framework, when the dismantling of the Federation of Korean Industries (FKI) and chaebol reform were the talk of the town, Kim served as the Moon administration’s first commissioner of the Fair Trade Commission.

Later, he also served as the Blue House policy chief when unexpected variables, such as Japan’s export restrictions on semiconductor materials and the COVID-19 pandemic hit the economy.

The Hankyoreh sat down with Kim on the morning of Aug. 22 at his research center at Hansung University. Two and a half years after leaving public office, Kim has now published a book titled “Global Economy in the 21st Century.” The book comes 11 years after his “Korean Economy 101.”

In those 11 years the original subtitle he’d been planning, “Korean Economy 101: Escape from the Chaebols and MOFia” (2012), was switched out to the new “New Normal or Back to Old Normal?” (2023).

As the change in the subtitle reveals, Kim tries to keep things brief so as not to sensationalize them, but in our interview, which ran on for more than two hours, the regret expressed in the book came through.

“Arguing that there is only one way forward, whether it’s in the form of a South Korea-US-Japan alliance or anything else, shows that one is out of touch with reality,” he said. “We need to learn from Europe, where rigid fiscal policy constraints are forcing government investment in the digital green revolution and cuts in social spending.”

The cover of Kim’s new book “Global Economy in the 21st Century.”

Kim stepped down from his post as the Blue House policy chief in March 2021 after controversy over the fact that he sharply raised the rent of an apartment that he owned just before the implementation of three laws aimed at protecting tenants’ rights, which limited rent increases to a maximum of 5 percent.

He was investigated by police following a complaint by conservative groups, but the case was closed without charges being pressed. This is his first media interview since leaving public office.

Hankyoreh: According to your book, “We can no longer misunderstand China as a country that imports general-purpose intermediate goods and uses its low labor costs as a weapon when exporting processed final products.” The recent South Korea-US-Japan summit also focused on the idea championed by the US that China is a threat. Do you think South Korea should also be keeping China in check?

Kim Sang-jo

: If that is how you read the book, that means you’ve misinterpreted it. If I had to pick one chapter for people to read, it would be Chapter 5, “Global Value Chain Shocks and the Division of Labor in Asia.” Through value-added trade statistics calculated from the world input-output tables, the chapter discusses how the world has become connected by the expansion of global value chains since the 1990s and how they are being reorganized, especially after the 2008 financial crisis.

Many people in South Korea still think of China as a country that lags in certain aspects, but we can see that this is not the case at all. Statistics show that China, like the US, uses less imported intermediates. It has completely transformed itself into a country that exports intermediate goods for other countries to produce. This is the most fundamental cause of the shift in the division of labor in Asia. Arguing that there is only one way forward, whether it’s in the form of a South Korea-US-Japan alliance or anything else, shows that one is out of touch with reality.

Hankyoreh: So you think that people asking whether Korea should be trying to put the kibosh on China to prevent itself from being sandwiched between powers are focused on the wrong question.

Kim: Lately it seems that every time we talk about international economic issues, the discussion becomes very much focused on how we are supposed to deal with the Chinese threat, but I think that’s only half the picture. US unilateralism is also a considerable threat. A prime example of that is the impact of the US Inflation Reduction Act. That legislation heavily subsidizes key minerals, electric vehicles, batteries, etc. in order to transition to a carbon-neutral society. The idea is to make domestic companies more competitive and build supply chains that exclude China. However, that act has disrupted the net-zero transition paradigm.

Europe has chosen a net-zero approach that imposes fees on economic entities that emit greenhouse gasses, as is demonstrated by carbon taxes and carbon border adjustment mechanisms. Obviously, when companies are charged a fee, they become less competitive. Every country now finds themselves in a subsidy race, but I don’t know if anyone can beat the US and China at this game. This has given rise to a significant amount of anger at US unilateralism in Europe.

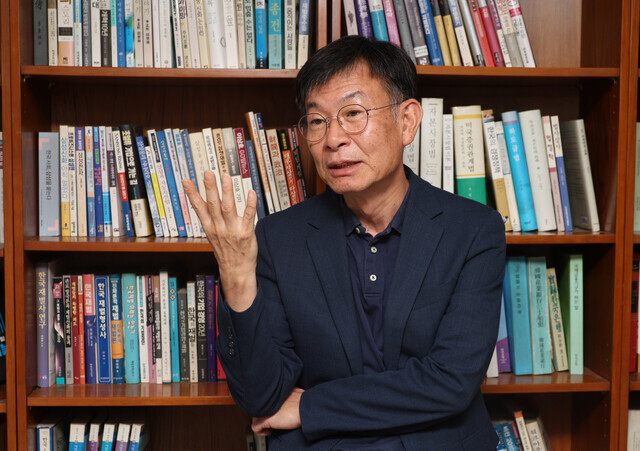

Kim Sang-jo, a former policy chief in the Blue House for President Moon Jae-in, speaks to the Hankyoreh about his new book at his office at Hansung University in Seoul on Aug. 22. (Kang Chang-kwang/The Hankyoreh)

Hankyoreh: So it would be foolish to see it merely as a showdown between the US and China?

Kim: That’s exactly the point I’m trying to make in this book. We shouldn’t forget the devastation wrought by the self-serving nationalism of many countries a century ago. That’s why I suggest that the current situation in the 21st century should be seen as a return of the “old normal” rather than the shocking introduction to a “new normal.”

The rise of China and America’s strategic responses to it all pose burdens and threats to us. If we are not extremely careful, the strategy we pick to avoid the costs of one may lead to us paying the price on the other end. As such, we need to flexibly adjust our strategy according to the situation, and the only thing that can help us is the support of the people. I’m not saying that leaving national security to the US and the economy to China is right or that the South Korea-US-Japan alliance is the best option. The conclusion I reached is that the government must make very careful and flexible judgments and constantly communicate with the public to strengthen its support base in order to achieve intended results.

Hankyoreh: How long do you think this will last?

Kim: I don’t believe that it will be short-term. Hegemonic competition, hegemonic transition — these are long-term processes. Take, for example, the issue of key international currencies. In the late 1870s, the US GDP surpassed that of the UK, US exports surpassed that of the UK in 1913, just before World War I, and financial activity in New York began to surpass that of London in the late 1920s. However, it wasn’t until World War II that the dollar became a true key international currency. It took at least 30 years and probably as long as 70, and the journey was not an easy one.

The world is changing much more rapidly now than it was then, so we’re looking at least another 30 years, if not longer, of hegemonic conflict. I don’t know if the winner of that conflict will be the US or China, or if there will be a compromise, but it was only in the 2010s, after the global financial crisis, that we began to notice that China was challenging US hegemony. So it’s been a decade now. That leaves at least another 20 years.

By Lee Wan, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [

english@hani.co.kr]